The Michigan Department of Corrections released their most recent Academic and Vocational Summary Report last week. Within the report there are elements to celebrate, areas of concern, and missing data that would help drive further programming improvements.

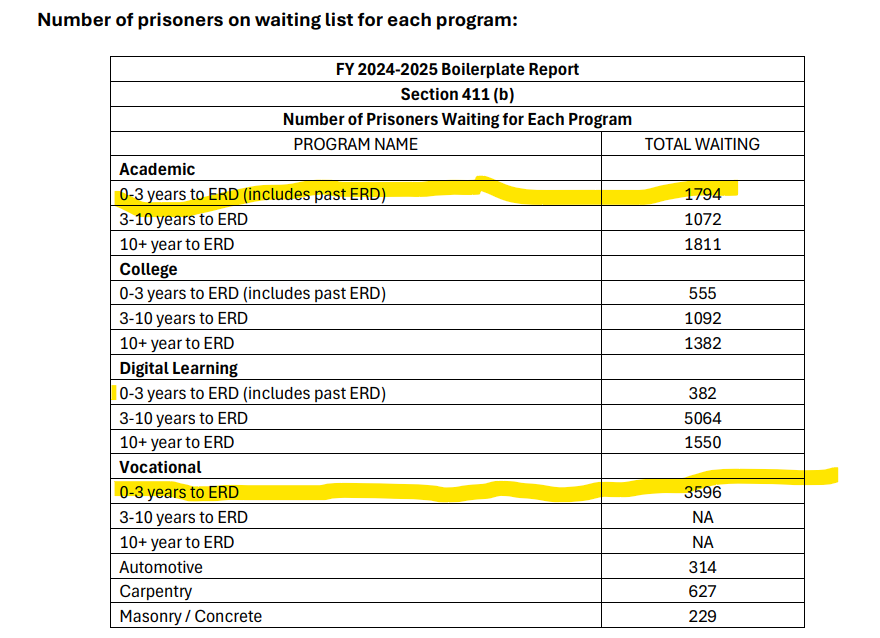

MDOC data show that large numbers of people are on waiting lists for academic programming (often GED or High School Equivalency), College, Digital Learning, and Vocational Training.

Wait times are too long for academic and vocational training

MDOC data show that large numbers of people are on waiting lists for academic programming (often GED or High School Equivalency), College, Digital Learning, and Vocational Training.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the report shows many incarcerated people with long sentences also unable to get into programming. One of the top complaints we hear among formerly incarcerated people is that they were given almost no access to programming until the last 6 – 36 months of their incarceration, then they were rushed through academic, reentry, and behavioral programming.

As vocational and academic programs are enrolled to capacity, fixing this is beyond MDOC’s purview alone. It would require legislators to increase investments in rehabilitation as a path to improved public safety.

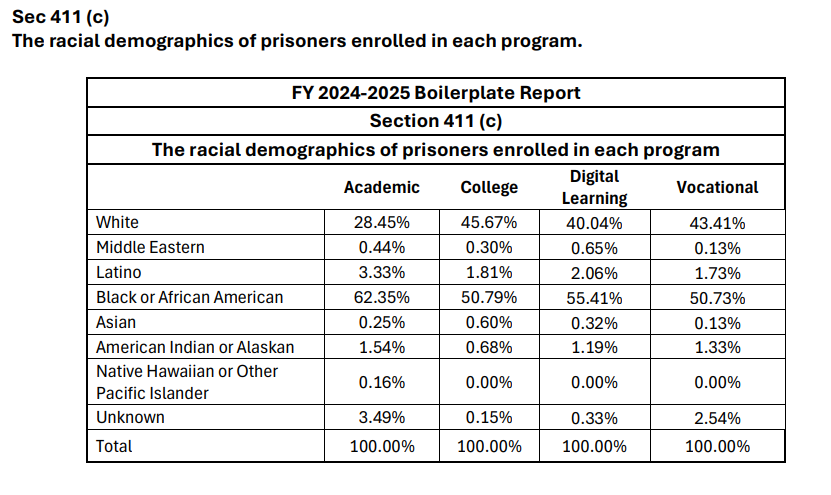

MDOC and its college partners have done a good job of preventing racial disparities in college enrollment

In the United States, African Americans are over-represented in prison and under-represented in college. The school-to-prison pipeline is alive and well for Black students.

In Michigan, African Americans are about 14% of the state population and about 51% of the prison population.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that within MDOC, African Americans make up 51% of incarcerated college students as well as 51% of vocational students. We do not see the enrollment disparities in prison that we do in the free world.

What the report does not show, however, are attainment or job placement data by race for these same programs. We do not know if there is a racial disparity in degree or certification attainment for the students enrolled in these courses or if there are racial disparities for who is able to attain a job in that field post-incarceration.

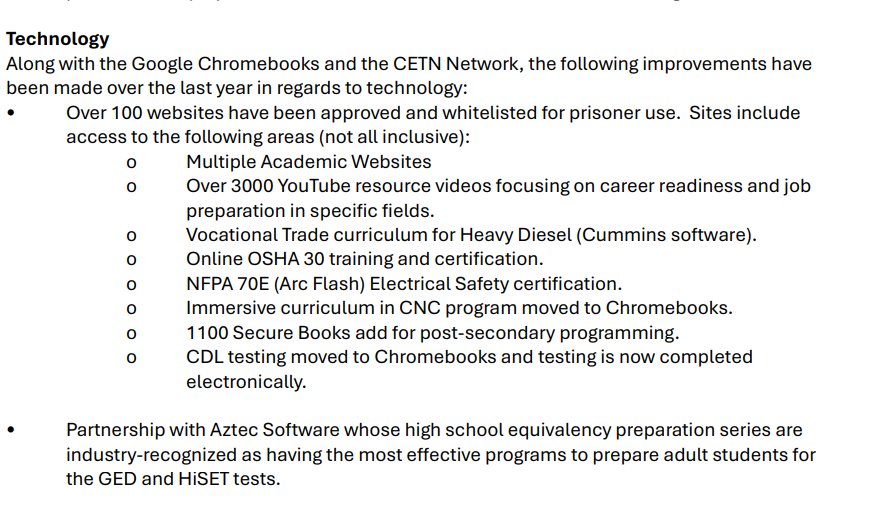

MDOC Reports Significant Improvements in Tech Access

Another chronic frustration among returning citizens is that they are unprepared for the digital demands of modern life.

Previous accounts of MDOC digital literacy efforts have reported out-of-date hardware and software, ineffective curricula, and limited access to using technology tools that would prepare people for reentry.

Against that history, MDOC’s increase in access to Chromebooks and Securebooks and the development of a secure network for digital access shows significant promise. That said, we have two caveats:

- Having the hardware and software is one thing, having access to it is another. Too often fancy new equipment sits unused in schools, nonprofits, and prison systems with the students unable to take advantage of the resources. Additional tracking, both by MDOC and by advocates, will be essential to assess if the tools are actually used and usable by incarcerated people.

- Digital fluency requires significant time trying out the new technology outside of formal classroom settings. Yes, a digital literacy course can teach you how to format a bulleted list or export to a PDF, but memorizing those steps doesn’t help when Google or Microsoft change their menus or when you need to figure out how to do something not on the curriculum. This requires time in self-directed experimentation with the tools, and departments of corrections in the US traditionally struggle to support that kind of unstructured learning. Our hope is that MDOC finds ways to ensure technology access outside of the classroom for incarcerated individuals to practice with the tools, whether or not they are currently enrolled in a formal academic or vocational program.

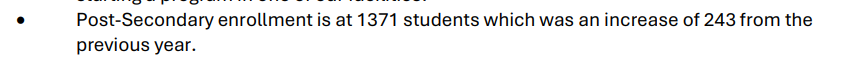

MDOC and Michigan Colleges and Universities Deserve Credit for Significantly Increasing Incarcerated College Enrollment

The rollout of the college in prison program has led to a 21% increase in enrollment by incarcerated college students.

College participation helps Michigan develop the skilled workforce we need for economic competitiveness, prevents recidivism, improves public safety, and anecdotally reduces prison misconduct.

MI-CEMI is grateful for the support for this program from MDOC, the participating Michigan colleges and universities, and from lawmakers who fund this effective public safety program.

The Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) and Michigan Department of State (MDOS) have made significant progress providing vital documents, and this program should be protected

In 2021, MI-CEMI surveyed Reentry Service Providers, vital documents were one of the top concerns

Too many people were returning to the community without a state ID, birth certificate, or social security card was a major issue. Lack of these vital documents impedes successful reentry by preventing people from getting a job, opening a bank account, or renting an apartment.

That MDOC & MDOS now report a greater than 99% success rate providing state ID or drivers license is a significant improvement, and our reentry partners also report that vital documents challenges are much less frequent than before.

That said, work on this front remains:

- The current improvements have been administrative changes by MDOC and MDOS. As such they could easily be rolled back by leadership in either department that does not recognize the public safety and economic benefits of these programs. Therefore we recommend that they be enshrined in law by passing HB5474, 5475, 5476, 5477

- While reentry partners do report significant improvements, anecdotal reports indicate the number of returning citizens who are job ready with all vital documents on day 1 is significantly less than 99%. This is especially true for people incarcerated from other states or who are released due to exoneration, resentencing, appeal, or commutation. As such, MDOC and MDOS should front-load obtaining vital documents to the beginning of incarceration rather than waiting until individuals approach their earliest release date.

Recommendations

- Expand programming access for people at all lengths of remaining sentences: The long waiting lists for programming undermine reentry success and may contribute to behavioral challenges in prisons. We encourage MDOC to continue to expand academic and vocational programming options system-wide.

- Expand academic support by using certified peer and college tutors. Prisons in Washington State have seen significant improvements in providing academic support for incarcerated GED students. In addition to the academic benefits, the use of certified peer tutors provides a high-value employment opportunity for incarcerated individuals and supports reentry success by providing returning citizens with a trusted educational accreditation.

- Expand academic reporting to include degree and certification attainment disaggregated by race. MDOC currently reports enrollment data disaggregated by race, which is a best practice, but does not provide clarity for educational outcomes.

- Codify vital documents provision standards: Pass enabling legislation to reduce the risk that MDOC and MDOS improvements get walked back.

- Expand technology access to all incarcerated individuals: MDOC reports significant improvements in developing prison-appropriate hardware, software, and network infrastructure. We hope to see that incarcerated people have meaningful access to these tools to develop digital literacy skills and other academic and vocational preparation for successful reentry.

- Expand reporting to include MDOC “core” programming and volunteer-led programming: In addition to academic and vocational programming, MDOC offers “core” programming based around cognitive behavioral therapy principles–programs that the parole board usually requires completion of prior to granting parole. Up through 1st quarter 2025, MDOC reported on these program participation and wait lists, but these reports have not continued. We encourage renewal of this reporting, as well as reporting if waitlists for core programs led to parole deferrals.

In addition, a significant amount of programming is through formal volunteer and peer-led efforts such as Chance for Life, Prison Creative Arts Project, 12 step groups, religious organizations, and others. These programs provide additional rehabilitative benefit with less staffing requirements. We encourage MDOC to report which formal volunteer and peer-led programs are operating at each facility.